© Livia Corona

We are excited to present today's conversation with current Guggenheim fellow Livia Corona.

I first became acquainted with Livia's work during the call for entries for Nymphoto at Sasha Wolf Gallery and I have been impressed with her dedication to her craft, commitment to her projects and her strong vision.

© Livia Corona

NP: Tell us a little about yourself.

LC: I live in New York and Mexico City—I think of the two as a single location, a kind of “Twin Cities” with a 5-hour flight bridging from one side to the other. I studied at Art Center College of Design. I am a photographer and sometime writer. I grew up in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico. From childhood until the age of fourteen, I traveled with my swim team, staying in the homes of host teams during swim meets in other parts of the country. Unknowingly, during my travels as a competitive swimmer, I was doing my own version of self assigned Field Practicum - Of this time I most vividly remember the family dynamics inside the homes I slept in, comparing them to my own home life, and noting ways one can get by, with and without problems. As a young adult, I studied art history in Europe while on study abroad scholarship. Eventually I moved to Los Angeles for art school.

© Livia Corona

In my current role as a visual artist, I am often familiarizing with new geographies, both for research and for commissioned assignments. My work is drawn by the underlying structures affecting quotidian survival, and my photographs expand on how these manifest on a broader level. Even though my approach to image making is not exclusively anthropologic, I think my photography, to this date, is a continuation of those sleepovers experienced early on as an in kid in a position that required independent, but under-aged travel.

© Livia Corona

NP: How did you discover photography?

LV: There were many moments pointing the way when I was growing up, but I chose to overlook them. I was always setting up photographs here and there, but I was opposed to photography as a career for myself because at that early age I did not know how I could transcend what I then knew of it: the two photographers in my home town only photographed events for the local social pages. I would notice how people would charm up to them yelling, “Shoot me! Shoot me! Put me in the paper”. Oh lord, the tension, I would think. I wasn’t attracted to the possibility of this chant as my life soundtrack when trying to earn a living.

My mother often visited a friend of hers who owned the one photo studio in the city. I would tag along on the visits and pass the time looking at the photo display cases, or hang out the back of the studio to watch how the photographs were being made. The owner of this photo studio was also one of my godmothers, and as a never-ending, very generous first communion gift, she processed my rolls of film for free up until my twenties.

In my early teens my mom and I went to watch a Luis Buñuel film cycle. There I saw a still photograph of a famous scene from “Los Olvidados” (The Young and the Damned). In it, the main characters, Jaibo and Ojitos, are beating up a blind paraplegic musician. The film of course made an impact, but more than the film’s subject I recall trying to imagine who the person who set up these scenes was. I think I experienced here for the first time that capacity of images to reveal perhaps as much about the preoccupations of the image-maker, as about the people portrayed in the images themselves. To simply notice this ability was a good sized step forward at that age, because it almost instantly informed me that there were other languages to communicate through, via the use of photography and narrative. It opened my eyes to listen for this unspoken language.

© Livia Corona

NP: Where do you find inspiration?

LV: It often shows up in research, or as I listen in conversations with or about the subject I am shooting. It is in these conversations that the images start to become clear. As we are talking I’ll think or suggest, “Let’s make a photograph that talks about that!” and I’ll propose an idea. Every image has its own solution. It’s a way to address a specific aspect of what can be an otherwise overwhelming topic, so little by little the story advances. Each shot is meant to stand alone, but collectively the images reveal a whole way of existence, even if seen one image at a time. Before the shooting begins, the people portrayed in my projects already know why I’ve decided to put a camera in front of them and they’ve decided if they want to participate in the story or not. I usually bring samples of previous work, or of the project I am working on. What I do is not straight on documentation, as I am asking people to perform a version of their lives to illuminate an aspect of a topic. One image cannot sum up an entire life. It’s a bit as if we are putting together a play in a small town, where everyone is pitching in to get the story made by the means available. Though I can turn shy about self-revelation and talking about myself in interviews, I am not timid about cohabiting the world of the people I photograph. My point of departure and influence starts from the inside, and it is natural to consider what is important from the perspective of whom I am photographing. Even when I don’t happen to agree with it, there is room to respond from within the image.

My research is almost endoscopic. It starts with one person, usually inside their home, talking a lot, considering every thing mentioned, even if unrelated to the final objective. People really inspire me. This doesn’t mean I like everybody, but it’s a real blessing, as there are so many of us about. And even when some of us aren’t very civil, my overall interest is more about the overall reasons that belie behaviors and social ideology. Why are things heading this way or that? Who’s fomenting this idea? Who and what raised us?

© Livia Corona

NP: How do your projects come about?

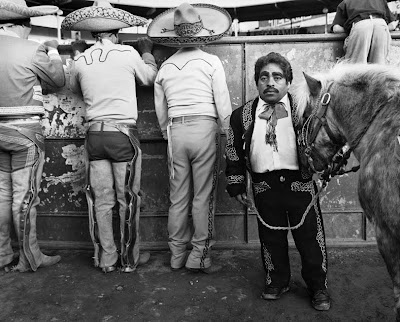

LV: Every project has its own catalyst. For my book Enanitos Toreros (powerHouse Books, 2008) it began very casually, when a woman, who has dwarfism and works as a comedic performer, invited me to travel with her group of dwarf bullfighters after I made her a headshot. For the book Of People and Houses (HDA, Austria, 2009) Andreas Ruby, a Berlin based architectural critic and theorist, saw my 2-4-6-8 series of photographs, made as an artist take of a very unique house in Los Angeles, and proposed a type of six week residency in Graz, Austria where I got to interpret characteristics of it most recent architectural projects.![]()

© Livia Corona

In my current work, Two Million Homes for Mexico, my drive comes from the riddle of what living in these neighborhoods can do to the development of a social and creative expression. What are the manifestations of this experience on the young minds growing up in these insular and remote landscapes, as they draw from a singular cultural and socio-economic backdrop? There are now more than 2.7 million of these identical homes built as neighborhoods all over the country. Who is behind this development model? How is it reconfiguring?

© Livia Corona

At broad glance the photographs of these houses, aligned row after row in such colorful and dramatic volumes, surrounded by mountain scenery, lit by a sunny Mexican sky, can remain in that realm of the pictorial panorama that a lot of contemporary art photography gets seduced by. As a visual artist it has been very important for me to transcend this aesthetic appeal, applying it just enough, when necessary, to engage the viewer into a close up view of what is happening inside these graphic and colorful developments. Developers provided infinite rows of identical 100 to 200 square feet homes. Dwellers are now faced with the task of turning the rows into streets and developments into cities. I am inspired by the inventiveness of people in these neighborhoods, who are adapting with a very hands-on approach—despite a limited infrastructure— to procure a more appropriate living environment. Mexicans, as other Latin Americans, are notoriously gifted in appropriating the built environment. My project both celebrates these small individual triumphs as it frames the challenges and abuses made in providing housing for an ever-expanding population.

© Livia Corona

NP: What’s next?

LV: I was recently awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which will afford me the opportunity to complete the project Two Million Homes for Mexico. I am currently in New York City, where I do part of my post-production. I love many things about New York; one of them is the efficient pace for productivity in the air that just gets in you. I work out of a small studio, along with two very talented studio assistants. Now we are in the process of a pre-final edit, and working on a book mock-up for presentation to potential publishers. Afterwards, I head back for a long road trip with stops in these housing developments throughout Mexico, hoping to identify and fill any blank spaces of aspects I want to cover.

NP: Thank you so much!

To see more of Livia work please visit: www.liviacorona.com.

Thursday, May 6, 2010

A Conversation with Livia Corona

Labels:

livia corona,

nymphoto conversations

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Wonderfully written and insightful- thank you Livia and Nina.

Thank you again Livia!

Post a Comment